Have any of you seen the Eric Rohmer film 4 Aventures de Reinette et Mirabelle? It’s sort of a retelling of the “Country Mouse, City Mouse” story. Two young women, one from the country, one from the city, are thrown together and become friends. They represent a certain sophistication and a certain innocence, which are respectively more simple and more complex than meets the eye. The first of the four segments, called the Blue Hour, is the most memorable one and what makes 4 Aventures still worth seeing, but I also recall a scene in which the city girl plays what to my ears is a pathetically bad euro-disco song on her tape deck and they both dance to it in the basement—and they have a wonderful time, with the country girl being thrilled to learn the moves. I think the song played in the trailer above is that song: very primitive rhythmically, melodically, tonally, put together in twenty minutes by some producer, a cut-rate imitation of the big-name synth groups of the 80s. A laughably barbaric musical regression of the sort only possible in modernity, and yet, for that moment, able to serve the girls’ high spirits and friendship.

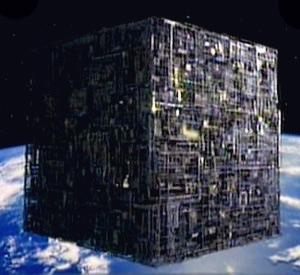

So that’s the first lesson: it is pointless to get all worked up about disco, about how bad it is, about how a bazillion ignorant people have “liked” Justin Beiber or T-ARA but hardly anyone knows about _________(fill in the blank). The fact is, some beautiful young person is probably learning to dance for the very first time to whatever disco tune it is you’re showering curses upon. I know, I know, on our bad days, disco can really seem a scary thing, the musical Borg that will assimilate us all.

Here for example, are a few fragments from Geoffrey O’Brien’s brilliant essay “Ambient Night at Roots Lounge” found in this book :

Everything became available anywhere anytime in a format of your choice. Maybe that’s why the World Music releases sound increasingly the same. It hardly seems to matter whether they originated in Andalusia or Mali or Albania, once the synths have done their work. It’s grist for the Body Shop, or for the changing rooms at Banana Republic. We’re all one, anyway, that was the idea, wasn’t it? The grittiness of actual silk roads and mountain kingdoms has been thrown into the blender. The undigestible bits—the parts that wound like maybe something bad happened once—lose themselves in a refreshing and indistinguishable tonic.

. . . In their virtual parade the ghost musicians go down the street blowing horns and banging the drums. It’s some kind of snakelike funerary process. Went by a while ago, actually. Don’t bother going to the window, they’re not there anymore. Fortunately, before they stopped playing, someone recorded the last bit of it. Someone else learned how to repeat the fingerings and mallet strokes and recorded their own version of the way they imagined it would have sounded if it had been properly recorded in the first place; remixed it; laid some heavy bass under it; fed it through the giant speakers into the thick of the dancers: and here it is.

. . . Imagine a planet where no one remembers how to make any of the sounds in the archive . . .

Now it’s time for even the last smeared images to go under. Here come the mutant headphones . . . . . . No songs have lyrics. Or they have lyrics like blank walls. I’m alone forever. The sun is on the lagoon. Welcome to the ice palace. The names are going . . . . . . .There is a sound like shapeless flakes. If you listen carefully you can hear the minerals the flakes were made from, melted-down chunks of disused temples, mountain zithers, murder ballads, genealogical anthems. We use history for body lotion. . . . There is a sound like gel . . . There is a sound like helium. Hard to remember words in the wind-tunnel. This tune you don’t hear, you climb inside it. Welcome to Surf City. It sounds better with the lights out. It sounds more like nothing, jacked up loud enough to make your bones rattle. You open and shut like a tent-flap knocked around in a cyclone. The howl modulates. The canvas flaps back and forth in the dark.

Yikes! Poor Mirabelle and Reinette sure didn’t know what they were getting into, did they?

But more seriously, if we ask the question, “Who’s Afraid of Disco Music?” Geoffrey O’Brien, who in his day-job as editor of The Library of America really is a keeper of our literary heritage, has to sheepishly poke his hand up and say “I am.” And I think if we’re honest with ourselves, not a few of us will poke our hands up also. His fears are not just the concoction of feverishly creative writing, but are frighteningly plausible ones. They are fears akin to the “salutary ones” we find sometimes in Tocqueville:

When I come to imagine a democratic society of this kind, I immediately believe I feel myself in one of those low, dark, stifling places where enlightenment, brought from the outside, soon fades and is extinguished. It seems to me that a sudden weight is crushing me, and I drag myself in the midst of the darkness that surrounds me to find a way out . . . Democracy in America, II, 1.9, #16

To update his dark imaginary place all we need is a disco ball and some bone-rattling bass.

Whit Stillman, by contrast, just loves disco. In part, this essay is meant to serve as preliminary before we look at his truly great THE LAST DAYS OF DISCO. Don’t worry, I’m not going to do a full job with DISCO the way I over-did it with ALMOST FAMOUS . Others, our Peter especially, have done very fine work on it already , so I will only address a couple music-scene-specific subjects raised by the film, specifically, classic 70s disco as a “movement,” and the aristocratic nature of the “Club.”

But before doing that we first need to think about disco as a music , and to recognize that there are two distinct ways of speaking about it:

1) Classic 70s Disco.

2) Disco in the Broad Sense—the family of disco-esque Dance Musics that start from 70s disco and continue on into the far future.

In common speech, and in this essay, both of these get called “disco.”

In the first sense, we speak of disco as a particular form defined by its mid-70s to early 80s pattern: a funk-based dance music designed for clubs, often with repetitious beat, usually deliberately sexy sounding, and often featuring strings or other features designed to give it a certain classiness. Funk stripped down to the groove, discarding the incidentals associated with a black-identity evoking funk fashion of churchy-bluesy raw emotion, and now more structured along pop-song lines. Stillman put together a soundtrack that features hits not only characteristic of the sound, but which stand as exemplary uses of it. A taste? And here’s a favorite of mine . What, you say you want “More, More, More?” Stillman’s film probably surprised many by being so unapologetically for disco, and it frontally confounded certain stereotypes commonly held about it, particularly those promoted by SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER and by the noxious 90s-era 70s nostalgia that loved to play-up all the t particularly gauche aspects of the era.

In the second sense, we speak of disco as a broader genre, as “dance music,” or what now seems to obviously be the most basic form of pop music, and one that will permanently be with us.

While the initial disco boom of 1975-1981 did dramatically “bust” market-wise as LAST DAYS portrays, and this did tend to make the disco style of those years rapidly seem anachronistic, one has to recognize that as a basic form , disco never died. Most obviously, rather disco-like songs continued to be huge hits: Kool and the Gang’s “Celebrate” of 1982, or Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” of 1984 come to mind. Less obviously, the early 80s “R+B” scene remained in large part a disco one. Yes, an increasing effort to follow hip-hop’s less repetitive (and yet more musician-impoverished) play with beats did gradually change this scene, but perhaps less so than some have suggested. How really different, for example, was a Boyz II Men circa 1988 from a Kool and the Gang circa 1979? Yes, the Boyz song is more complex rhythmically and structurally, but isn’t the welcome-all simplicity and smoothness of “Ladies’ Night” also appealing? Are we going to make a huge distinction between the two, and say the one is hip-hop, and the other disco? Well, many expert advocates of hip-hop have said that, and it works as far as it goes, but wouldn’t it make as much sense to say that the Boyz II Men song is a good disco song? More on that possible distinction in a moment.

We must also note that a big trend for many white listeners in the early 80s was New Wave, and a major part of this scene (for a discussion of the other parts, look-a- here ) was the techno-pop dance club scene. Yes, following certain Euro-disco cues, these clubs emphasized highly futuristic music—the godawful Kraftwerk was the ruling muse. So one wanted to imaginatively “Travel” into a mechanistic Germanic future by “Riding on the Metro” more than one wanted to board any soul-fueled “Love Train,” and (rather rock-esque) avant-garde instincts could and did take this further, into the veritable musical hells writers like this one actually celebrate. But at the end of the day, 80s techno-pop was still shaped by what worked in the Club to drive the Dance, even if the reductive aesthetic at times sure did make it seem like these clubbers would dance to anything . It’s preposterous to deny that Aha, The Human League, The Thompson Twins, Howard Jones, Yaz , Madonna, etc., etc., were not disco . At least in the broader sense. And today, we should say the same about K-Pop and such.

In the long view, what characterizes this disco in this second and broad sense, is pretty much as follows(I’ve said as much before in Songbook #s 11 and 39 ).

1) The producer or the d.j./collage-artist tends to replace musicians through sound compositing or synthesizing techniques; if he does employ musicians, he tightly binds them to his structure.

2) This usually means that the disco recording is both cheaper and easier to produce; and obviously, it is always less expensive for dance-clubs if they can satisfy their patrons with recordings as opposed to live acts. The other convenient thing is that disco makes interaction of cultural differences easier—it is the international style , musically speaking, even though we know that its roots go back directly to Afro-American R+B.

3) Particularly in its various Euro-disco offshoots, the music often reflects a reductive attitude and fatalistic futurism about music.

4) The story of disco’s initial development is one in which a primitivist (and ultimately racist, although embraced by plenty of blacks themselves) attitude that sees sexual abandon as the heart of Afro-American music eventually transformed the music. Mission “Make the Music More Consistently Sex-Evocative” was, alas, Accomplished, although arguably without making things truly sexier, despite more moanings, whisperings, etc.

Martha Bayles is particularly strong in showing how a general overdose of hedonism in the late 60s and 70s over-sexed and over-drugged the music, at expense of the swing, giving us hard rock on one hand, and disco on the other. But we are going to have to supplement and qualify her account with what Stillman emphasizes. And we are going to have to insist that whatever message this conveys to adults who are aware of pop music’s less-robotic and less-sex-evocative past and possibilities, it is often musical innocents who embrace the genre, because . . .

. . . 5) Disco is easier to sell to inexperienced listeners and dancers, and a number of technological developments, such as video and internet proliferation, have aided in this. Young folks are less and less experienced with the communal reception of music that can only occur live, and thus haven’t developed the taste for the magical exchanges possible, particularly in the Afro-American tradition, between a swing-capable set of musicians and a tuned-in audience. And if all they experience is disco, alas, they never will develop this taste.

But sigh as we might, we must admit that disco dancing is better than no dancing. In times and situations where the musicians are rare or cannot be brought together in an economically viable way, the convenience of disco is its most compelling excuse.

And as I’ve suggested, disco can be done well. And when it is, when it begins to rise above the limitations sketched above, there’s often a tendency is to insist that it is not disco. Three claims can be made here.

a) Advanced music-mixtery techniques, the musical collage art pioneered by the hip-hop DJs and the saaviest producers, and which arguably culminate in mash-up, takes the music to another level. It is no longer pop, and no longer disco.

b) Hip-hop in general does the same thing, but not by its mixtery and sampling, which is incidental to the core sound, but by its heavy emphasis on the funk and the rhythmic complexity.

c) Disco began with live musicians, coming out of the funk tradition, and there is no reason it cannot develop back in that direction.

I reject a). If the beat remains repetitious and unswingin’, no amount of mixtery-complexity layered on top can alter its basic nature. Neither can lyrical or any other artistic sophistication. Here the hip-hop advocates and the roots/jazz advocates are in agreement.

Hip-hop is too complex a phenomenon to adequately discuss here, but I think its advocates have to admit that for far too long, hip-hop tended to kick the live musicians out, and so especially live, its jerkier rhythms could never cook as ably as older Afro-American ensembles in the blues-swingin’ tradition. We have long been hearing that the barrier against live musicians in hip-hop may be changing , and I want to hope so as much as anyone, but somehow the more live-musician friendly hip=hop never breaks through. My suspicion is that hip-hop remains at bottom more linked to a reductive disco spirit than its advocates want to admit, and that part of the problem goes back to funk itself. Too much pot and crack-pot Afrocentricism made folks too open to the strangely addictive nature of the funk groove, at the expense of the melodic structure that had always also been part of the Afro- American tradition.

A huge subject, that, but like Bayles, I have a lot of respect for the funk bands, and of course the ensembles led by James Brown most of all. And as I listen to 70s disco, I can’t help but notice that the musicians were still very much part of the phenomenon. With some groups this is more obvious than others. One could argue that rather than the John Travolta character, or the Chic-ed out Disco Club, the true icon, the most symbolically archetypal icon, of 70s disco was Janice Marie Johnson, the bassist and singer for Taste of Honey . In the link you see her playing her group’s hit live, looking as drop-dead glamorous as any female disco star, and also playing some mean bass a la Bootsy Collins. She’s no disco-dollie, but a decidedly black woman who can musically stand on her own feet—her also being beautiful and sexy is merely the cherry on top. R+B-rooted funk music and the live chops necessary to really deliver it, sophisticated beauty, cross-over appeal bringing blacks and whites together but not on musically watered-down terms, she’s got it all.

Make no mistake, disco will be with us until the end of time, and depending on your theology of hell, certain forms of it may be eternal. From the moment Edison invented recording, various trends were preparing the way for it, and its full advent in the 70s and 80s was inevitable. Certain folks will always be figuring out that it can be made better, more like the R+B, soul, and funk it came out of, insofar as one brings live musicians thoroughly trained in Afro-American music into the “mix,” and into the “command booth,” so to speak. Various Dee-lites of that sort will always remain possible, and always ready to push back against robotic rhythms and canned sounds while winning over the dancers that have become used to them. One can hope that in our time, given the long dominance of pretty bad forms of disco, given the popularity of artists like Amy Winehouse and Adele,and given a growing movement in favor of older recording and composing techniques, that a more serious push-back becomes possible, bringing us to the point where we might again be moved to call our dance music soul. Yes, the petering out of certain lines of musical apprenticeship do mean that certain elements Afro-American musical artistry may have been lost forever, but so long as we still have musicians, there is cause for hope.

But always, even in the midst of the most robust of musical renaissances we could possibly hope for, somebody is going to find some ignorant millions of Mirabelles and Reinettes somewhere to sell his latest crude computer composition to. The dance, and the fight for a more civilized (and swingin’!) way to feed it, will go on.

You have a decision to make: double or nothing.

For this week only, a generous supporter has offered to fully match all new and increased donations to First Things up to $60,000.

In other words, your gift of $50 unlocks $100 for First Things, your gift of $100 unlocks $200, and so on, up to a total of $120,000. But if you don’t give, nothing.

So what will it be, dear reader: double, or nothing?

Make your year-end gift go twice as far for First Things by giving now.